How Technology Deployment Drives Authoritarian Populism

For a couple of years, our societies have been driven by two forces: Populist parties and civil movements.

Authoritarian populism has been regaining strength all over the world: Trump in the US, UKIP in the UK, Bolsonaro in Brazil, and the AfD party in Germany are just a few recent examples.

According to the Timbro Authoritarian Populism Index, the average share of votes for authoritarian populist parties in the EU stood at almost 27% in 2018. This represents a new peak of support for populism, which is not limited to the EU but has formed globally.

At the same time, we are witnessing the increasing power of civil movements. I believe that we haven’t seen any time in history when so many citizens rose up to protest: France, Lebanon, Hong Kong, and Chile are examples on a national level; #MeToo and FridaysForFuture are recent global movements.

What do these two forces have in common?

I believe that they are the results of technology deployment. This essay will lay out the causal web of this hypothesis. As always, I hope that my readers will drive this forward one way (add) or another (push back) #populismdeployment.

Short Foreword on Technology

This essay refers to technology in a broad sense.

I don’t mean to discuss how social networks are driving filter bubbles or how algorithms can be used to engineer splits in society.

Technology has a profound impact on our society that is far greater than any individual company or product.

From Innovation to Deployment

Every successful innovation needs time before it can change the fabric of our lives.

When Benz built his first car at the end of the 19th century, it was inferior to a horse on almost all dimensions. It was more expensive, higher maintenance, less powerful, slower and offered a less comfortable ride. After all, most streets at that time were horse tracks. Try driving an older car on one of those. You’re in for a very bumpy ride.

In a world where everything is optimized for the horse, a car doesn’t make sense.

It took years of incremental innovation until the car became clearly superior to any horse. The resulting demand changed the whole world: Petrol stations, asphalt roads, city layouts, drive-throughs, supply chains - literally the face of the earth was altered by the deployment of the car.

We are living in a similar phase of the technology cycle today. We are living in the deployment age of digital technologies.

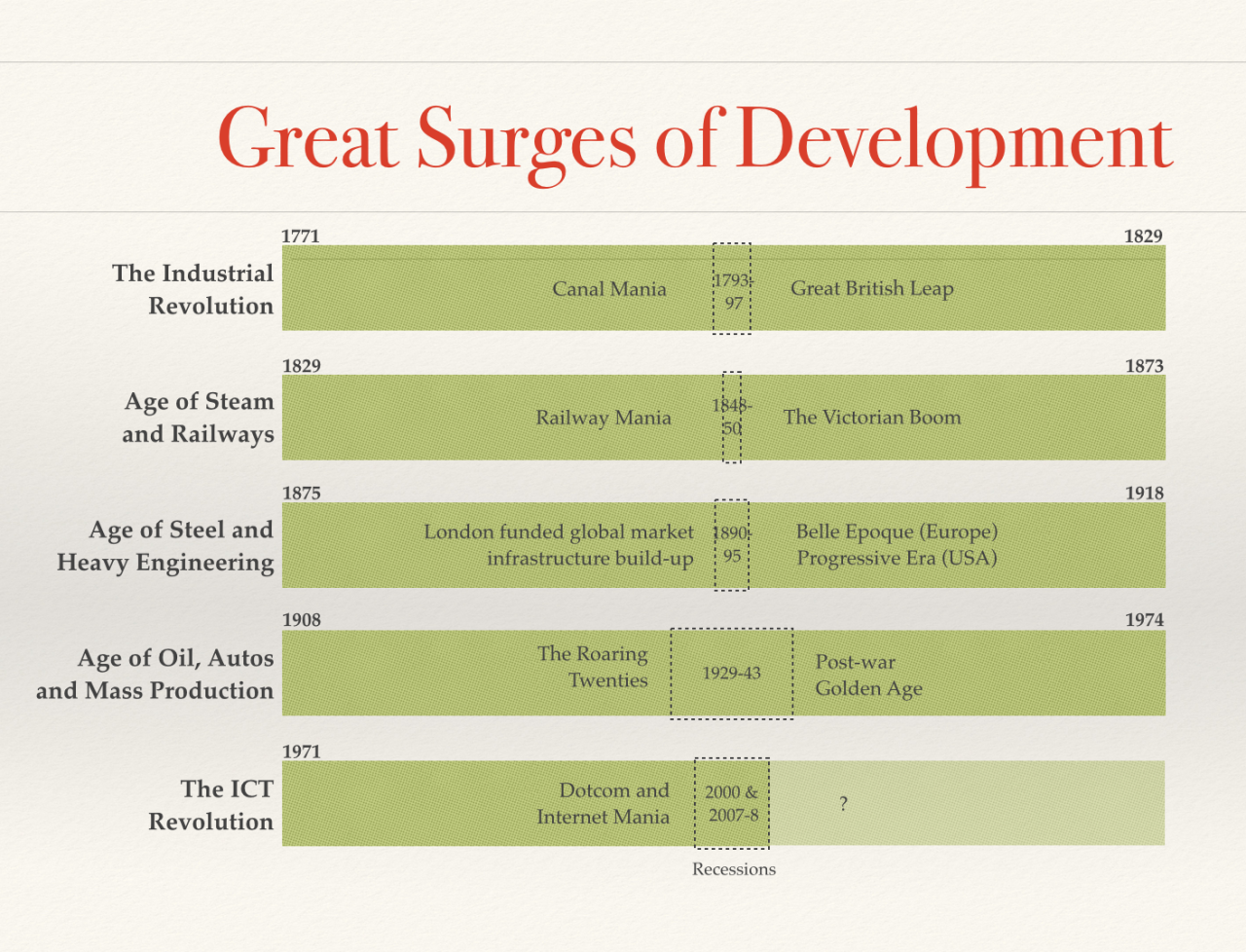

Carlotta Perez has coined the term deployment age. Her theory shows the complete cycle an innovation goes through using examples from the last 200 years.

She describes how innovation needs time to develop an ecosystem. During that ecosystem development time, more and more capital is allocated towards the innovation. Perez lays out that the innovation part of the cycle ends with a bubble bursting and a recession.

This happens around the time when the ecosystem becomes ready. Afterward, financial capital shifts to expert capital as the innovation is being deployed widely. It simply becomes the new normal.

Digital Deployment

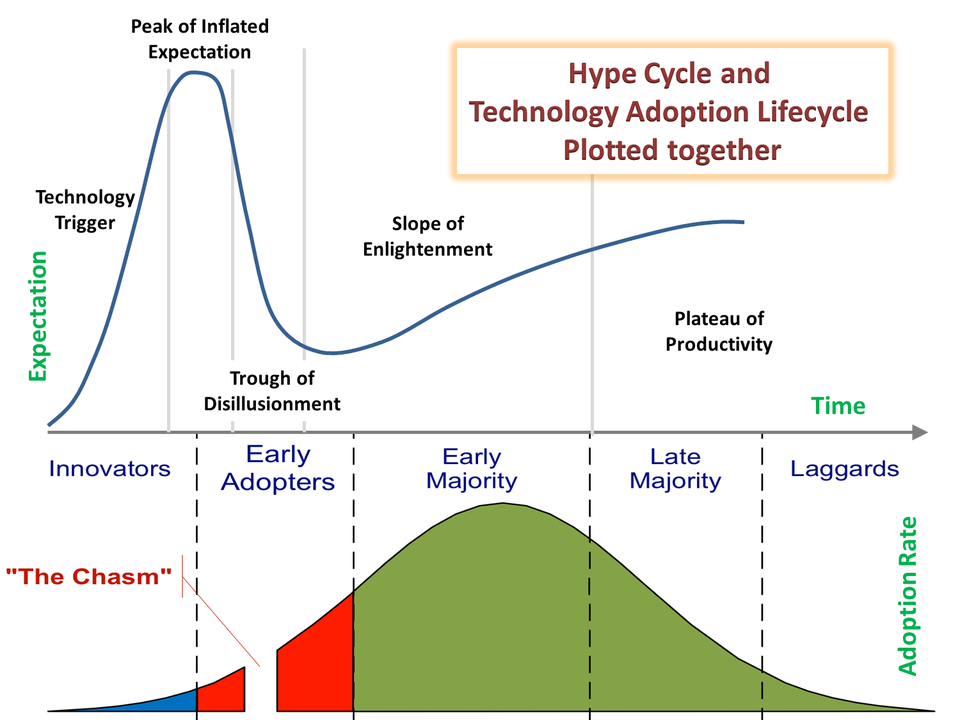

While digital technology has arguably been used for over 3 decades, it has now entered the plateau of productivity.

As we progress further into the plateau, adoption rates are increasing fast: It took the internet 7 years to reach 50 users. Pokemon Go did it in only 19 days.

In the timeframe of 1990 - before 2010 incremental innovation on top of the digital technology - coming up with access points (browsers), infrastructure (cloud), technology standards (W3C) and endpoints (smartphones) - completed the ecosystem: The set of technologies became coherently organized and interconnected as a platform, which enabled others to built on top of it.

This is why the focus has shifted from innovation to using what has been developed to transform the face of the earth yet again.

The car has raced past the horse.

The Transformation of Everyday Life

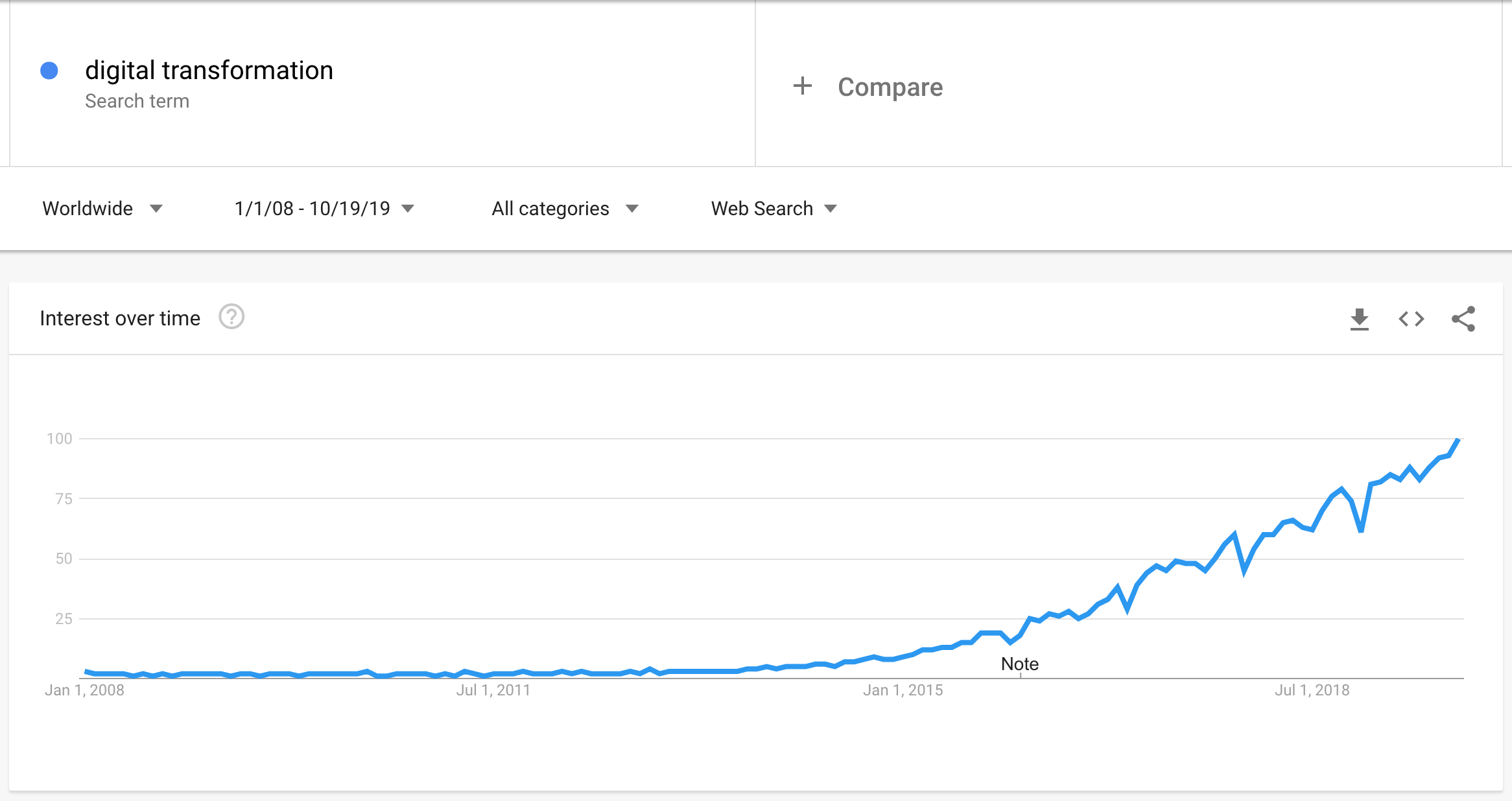

Until five years ago, nobody was talking about digital transformation. Nowadays, you can’t attend an event in any industry that doesn’t have a panel on it.

The first industries that were transformed were the ones closest to the digital world: Publishing, music, media. They represented the low hanging fruits, as moving information was central to their value chains and that information could easily be put into a digital representation.

Now, the deployment of digital technology is happening in all industries, even those that are profoundly non-tech.

Software is eating the world after all.

The important point is that digital technology has now started to change the fabric not only of individual companies but of our societies and lives: Education (e.g. Lambda School), government (e.g. Palantir), healthcare (e.g. American Well), military (e.g. Anduril), banking (e.g. N26) and dating (e.g. Tinder). Every year, digital technology is moving faster and closer towards everything we do and touch.

Whereas relatively few people were affected by the transformation of the publishing or music world, today almost everybody is touched by the transformation at work and at home. The deployment of digital technology is now perceived by everyone.

Let’s summarize the two takeaways:

- The rate of change has dramatically accelerated;

- That change is now perceived by everyone.

Change ≠ Progress

As the name implies, deployment is about applying the same finished technological system as widely as possible.

So it’s not surprising that all examples mentioned above are not innovative in a strict sense.

They are “merely” successfully deploying existing technology. They are combining what was already out there in the right way.

Industries from military to music are changed by the same underlying technology ecosystem, the application of a handful of business models, distribution channels and playbooks.

Deployment does not create new industries. It does not bring progress or even overall growth. It turns the ocean red, as digitally-enabled companies eat those that did not use the full potential of the digital technology system.

Deployment does not create anything new in itself. Creation happens in the innovation cycle that precedes deployment.

In spite of all promises about self-driving cars, robots, and travel to Mars, real breakthrough innovation felt absent over the last couple of years. Now we know why.

In fact, life today does not look so different from life in 1988, the year I was born.

To summarize, change is increasing, but it is not driven by innovation at this point.

We are all currently living through the age of deployment, the age of change without progress.

Überforderung in the Face of Change

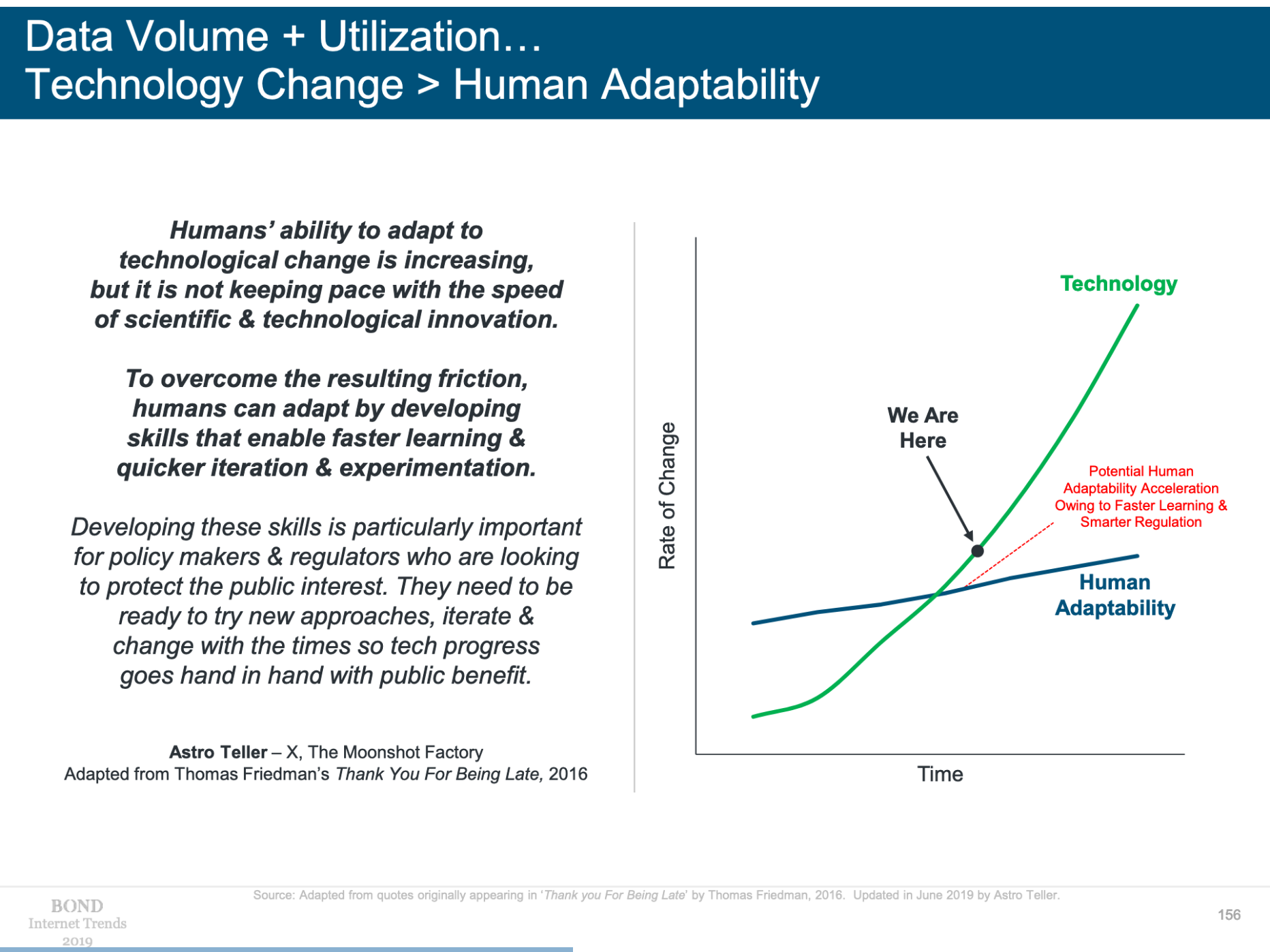

In her Internet Trends 2019 report, Mary Meeker included one slide that schematically showed that the rate of change has outpaced human adaptability.

Although her slide states, that the cause of the change is innovation and not deployment, I quite like her illustration.

The increasing deployment of technology has already left the majority of people behind.

In an environment, where people can’t keep pace, can’t adapt fast enough, they quickly feel “überfordert”.

Unfortunately, there doesn’t seem to be a perfect translation for the German word “Überforderung”.

The closest I could come up with, is the combination of being overstrained, out of one’s depth and losing control.

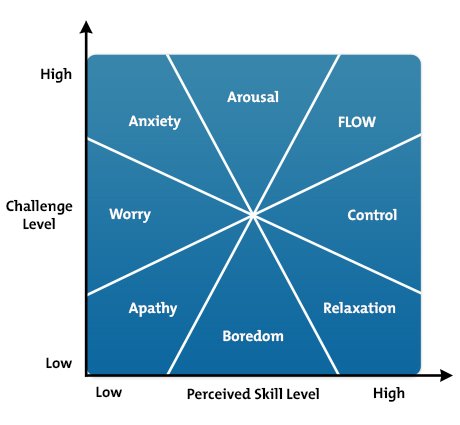

I find the Flow Model by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi a great framework to describe the emotional state of people in different environments.

In an environment where the skill level is higher than the level of the challenge, people are in control. They feel everything from boredom, relaxation, and control all the way to flow.

In an environment where the skill level is below the level of the challenge, people loose control. That’s when they are überfordert. In such a situation, the emotional state is described by arousal, anxiety, and worry.

Isn’t this an apt description of the emotional Zeitgeist?

But it’s not just that the majority of people got left behind and feel this way on an individual level, what is probably even more problematic is that all of this applies as much to institutions.

Due to traditional career paths, the majority of leaders in public institutions belong to and cater to the majority. They understand the majority’s problems and fears that are triggered by the rising tide of change. The majority’s problems and fears are their own problems and fears after all.

From Determinism to Indeterminism

It wasn’t so long ago that leaders had clear goals and messages. CNN summarised 2004 in the following way:

“In many ways, 2004 was a yearlong campaign complete with winners and losers, rhetorical and real attacks, and concerted efforts to reach lofty goals.”

(bold formats are mine)

Let’s compare that statement to the 2018 summary, where one of the selected top worldwide developments was that South Korea closed its largest dog meat slaughterhouse:

“Well 2018, it’s been real. We had our good times and our bad times – and our strange times in between. We can’t say you were our favorite, but we’d be ungrateful if we didn’t give props to the good things you brought.”

We went from concentrated efforts to a Spaghetti of emotions. In just 15 years, the world changed from determinism to indeterminism.

In an environment where the majority feels increasingly überfordert, it’s clear that people have an increasingly harder time to make up their minds and find solutions.

What does it mean when government bonds naturally pay negative yields?

It means that the markets think that governments don’t have good ideas of how to allocate capital. They have no idea of how to use money to fix stuff!

In an indeterministic world, they don’t.

As the increasing rate of change due to deployment has outpaced the majority of our societies, individuals and governments have shifted from determinism to indeterminism.

From Optimism to Pessimism

Historically, change was a result of innovation.

The last century was characterized by an unprecedented development of new industries: Cars, planes, TVs, movies, pharmaceuticals, etc.

Innovation leads to the development of something completely new which drove growth. Change was always part of life, but it lifted people up. It created new jobs and solutions to previously unsolvable problems for the majority. It made the majority of people better off and more affluent.

But that doesn’t hold any longer.

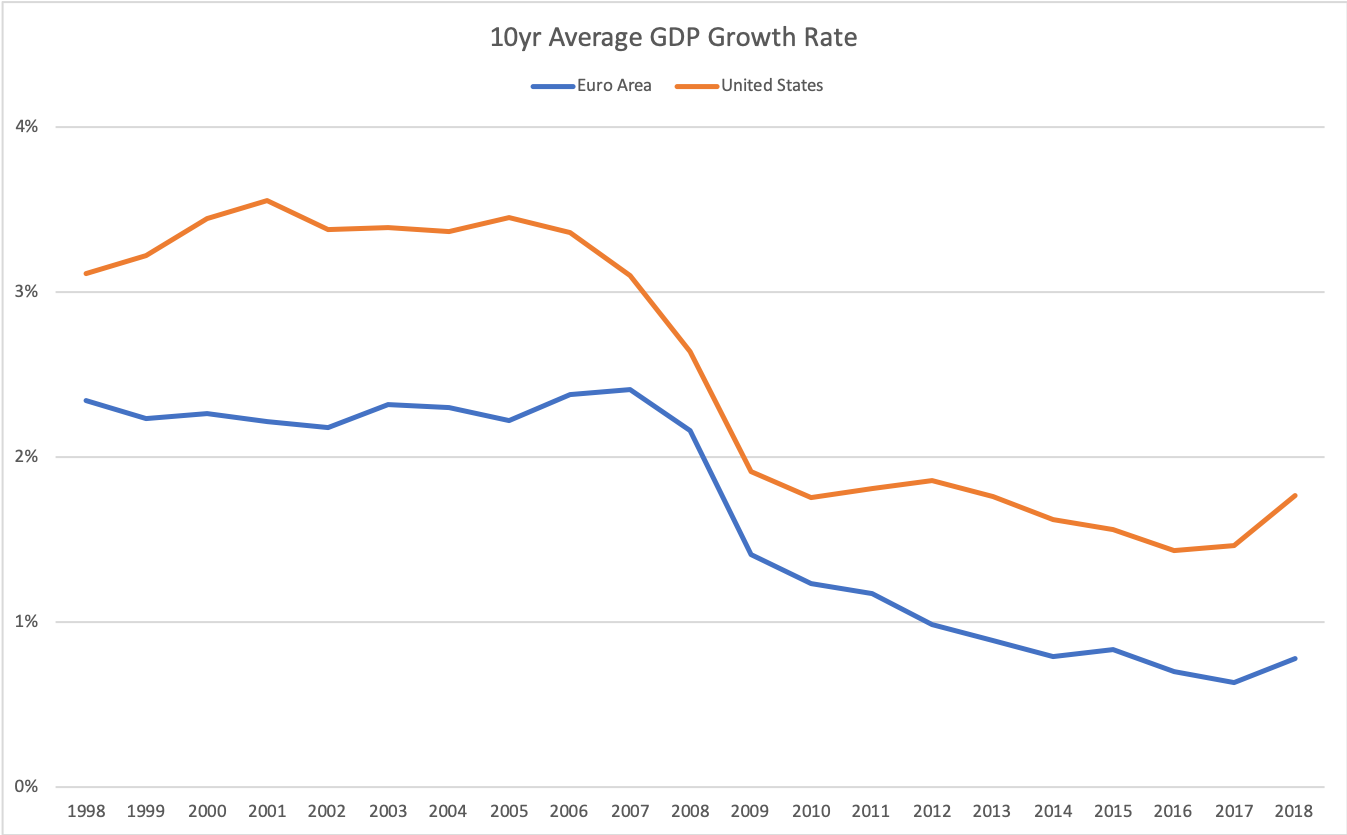

10 year average GDP Growth Rate - Source: The World Bank

As previously stated, we live in the age of change without innovation. Although the rate of change is at its peak and increasing, growth doesn’t follow as it did traditionally.

Deployment doesn’t create new industries. It exchanges old with new. Only the small minority who can still cope with this rate of change is able to drive the deployment. The majority can’t participate in this development.

When change is driven by innovation, it makes people better off and makes people optimistic.

When change is driven by deployment and the majority can’t participate, it makes people pessimistic.

Thiel’s Matrix

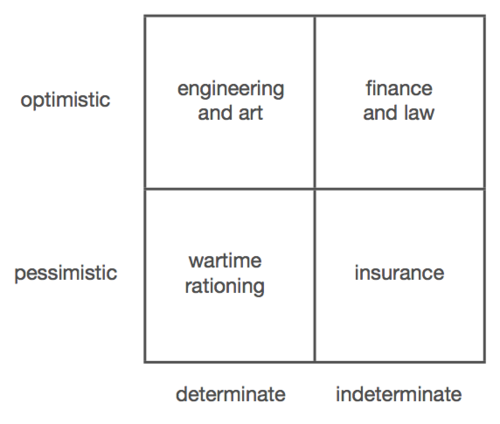

The idea of the determination vs. optimism matrix comes from Peter Thiel’s legendary CS183 class in 2012.

Bringing it all together: The age of deployment has created the shift from determinism to indeterminism and from optimism to pessimism.

Now, what does all that have to do with the rise of authoritarian populism and FridaysForFuture?

The Lack of Leadership

In an indeterminate world, leaders don’t lead, can’t lead.

The implicit contract in democracies is that people assign power to the representative government. In exchange they expect the government to make decisions that improve their lives.

As the world turned indeterminate, leaders can’t fulfill that contract any longer.

As a reaction, to stay in power, leaders have changed from leading to listening.

Try to find a clear message or a clear goal in the programs of democratic presidents. “Yes We Can” is decidedly vague.

The German majority government has become a giant echo chamber. It tries to playback any message that they hear.

The problem is that politicians are listening to people who are themselves indeterminate. Politics has developed into a delicate dance between two blind strangers.

The pessimistic indeterminate majority is searching for a solution, which leaders can’t offer them. Governments are concerned with managing the past, where they have competencies. Instead of finding solutions that work in the deployment age, the German government would rather fix more roads. Instead of building the required digital competencies to allow more people to keep pace with deployment, the world is concerned with tariffs.

Determinate Messages Dominate in Indeterminate Settings

The civil disobedient shares with the revolutionary the wish to “change the world,” and the change he wishes to accomplish can be drastic indeed.

— Hannah Arendt

The majority of people realize the lack of leadership and representation. This pushes people to stand up and become active. Anybody with a definite plan or clear message has an advantage in such an environment.

Unfortunately, authoritarian populism offers a simple and clear message. Instead of realizing that the cause of pessimism is the change driven by deployment, they assign it to immigration, foreign trade or the conspiracy of minorities.

Their message is simple: “Stop immigration, protect the nation, more rights for the majority!”

Since their clear messages resonate with the majority, populists use the traditional permissioned power tools of the past to gain power. They vie for positions of power (Trump) or create new political parties (AfD in Germany).

A more positive example is the voting results of the Green parties across Europe. They also offer a clear message: “We protect the environment.” They haven’t changed this message for decades. But now in the indeterminate, pessimistic environment their clear message travels further.

Successful populists come from the majority. In many cases, they have been insiders of the traditional systems of power. This is why the traditional route to power comes naturally to them.

The minority who drives and can cope with the change (let’s call them “digital natives” here) understands the world that has emerged. They see the real challenges ahead and demand real solutions.

Just as much as the majority, this minority doesn’t feel represented any longer and becomes active, too. They, however, don’t have access to the traditional systems of power. Due to the demographic changes, this minority faces an increasingly thicker glass ceiling inside the institutions.

This is why the “digital natives” use the permissionless distribution of digital technology to gain influence by applying permissionless models of power (movements).

FridaysForFuture is one example. It resulted from a minority feeling that a major problem is “the lack of action on the climate crisis” and creating a movement to demand action.

Where do we end up?

It’s clear that the indeterminate, pessimistic state can’t be a final, stable state of society.

Active people with determinate ideas are increasingly being heard and are building a following. They are using two methods: Permissioned government and permissionless movements.

The question is, do we end up in the determinate pessimistic quadrant or can we reinvigorate innovation or implement the right regulation to lift us into the determinate optimistic one?

What can you do to make the optimistic outcome more likely?

A big thanks goes to Bobby, Steffen and Caroline for reviewing an early draft of this essay and for your input!

Feature photo by JD X on Unsplash