Using Mimetic Theory to Explain Herd Mentality in the Venture Capitalist Industry

There is a famous idiom in the English language that fits well with the ideas of René Girard. It perfectly encapsulates the nature of desire as well as human relations: Keeping up with the Joneses.

Bear with me as I first describe Girard’s theory of desire and afterward go into its relevance and applicability for marketing and fundraising.

According to Girard, desire is neither straightforward nor autonomous: I am not buying that new 65 inch, smart, 4K, OLED TV because I want it. Rather, I need it because my neighbors just bought a new TV.

Girard didn’t set out to become an anthropologist. He taught French literature in the US. It is in reading and analyzing the great literature that he uncovered a common theme. He found it in works from the Bible to Cervantes to Dostoevsky to Shakespeare.

The commonality between all of them was something simple but profound. As with so many eye-opening ideas, it’s surprising that nobody had articulated it before him: Imitation is the central mechanism of human behavior.

Man is the creature who does not know what to desire, and he turns to others in order to make up his mind. We desire what others desire because we imitate their desires. — René Girard

Reading Girard in this day and age feels like going squarely against the zeitgeist. Our society feels very much invested in the final belief of autonomy and free will.

We are, after all, conscious and in control of our fortunes, right? There is no divine power that determines our behavior. Isn’t that so?

Mimetic theory of desire

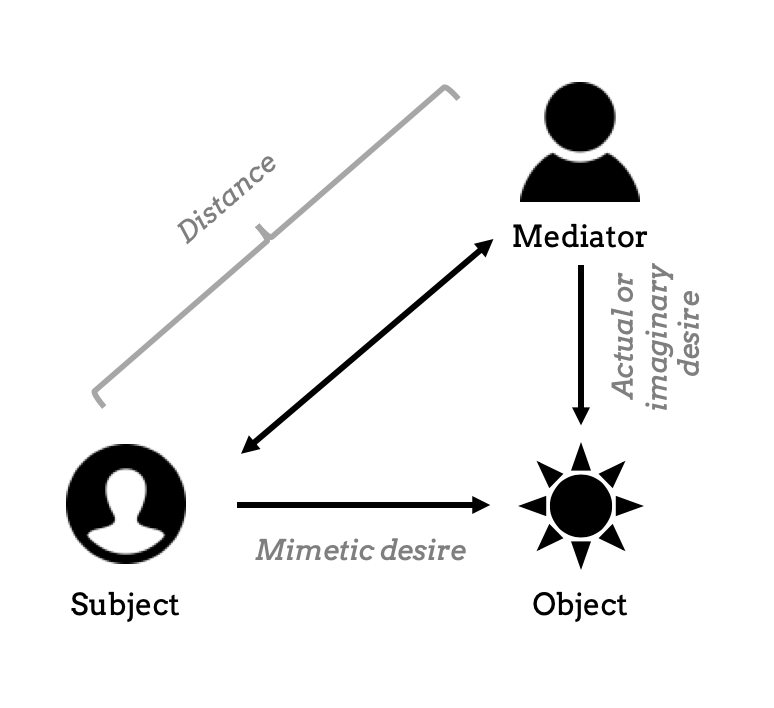

What Girard discovered in the literature was quite different. The subject desires an object through a mediator. Desire stems from and is mediated through a third party, forming a triangle. The origin of desire is the mediator. We imitate him. This is the mimetic part. At the same time, the subject, object, and mediator form a behavioral triangle of desire. This is how we arrive at the final form of the theory:

Desire is mimetic and triangular.

What a fancy way to put it!

As humans, we possess the intelligence to control and determine our environment. As such, we are exposed to much more optionality than our animal predecessors. As everyone who’s ever stood in front of the shampoo section in the supermarket knows, choice has its price. And when there’s too much choice, I just don’t want to choose anything.

A simple heuristic is to choose what others have chosen. Their decision provides us important information about the world. Copying them is relatively easy, making the cost of acquiring that information and making a decision rather low. As long as somebody else desires an object, it must be valuable / nutritious / non-poisonous, etc.

Imitation has been helpful for survival. It is also our natural way to learn. Babies imitate parents and TV shows.

Babies also imitate each other. Tommy, 17 months, is perfectly happy playing with his wooden train. His parents have invited over another couple and their child Emma, 15 months. Emma discovers Tommy’s plastic guns and starts playing her very own version of High Noon.

Although his guns were available to Tommy before, now that the Emma is using them, somehow they are more desirable. Conflict emerges.

Long or Short Distance Relationship

We are social animals who live in social hierarchies. Possessing an object that others desire increases our status. It elicits envy, jealousy, and rivalry, as perfectly demonstrated by Dinesh’s reaction to Danny’s superior Tesla purchase.

That’s not always the case, though. Conflict is a function of the distance between the subject and the mediator. In Girard’s context distance does not refer to the physical distance, but the social one. That’s a key part of Girard’s theory.

Madame Bovary dreams of the romantic and luxurious society in Paris that she knows from her novels. She acknowledges that her desire is derived from these books and stories. Her mediator is external. She is trapped in a village and by her simple farmer heritage. She has no chance to ever become a Parisian It-Girl. So she yearns instead of feeling envy.

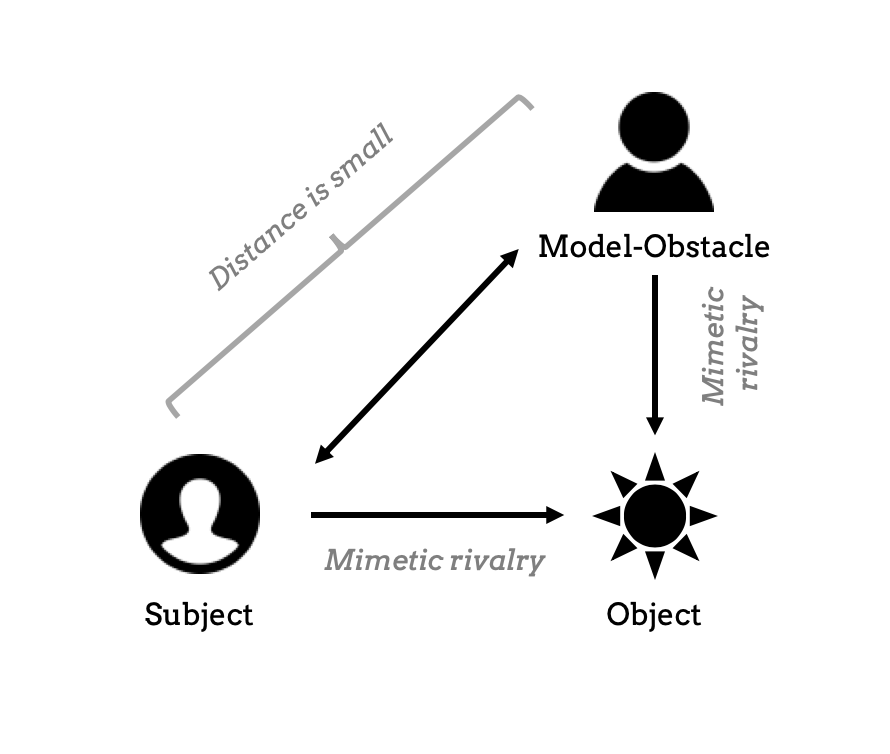

When the distance is small, desire starts to operate at a subconscious level. In these cases, it leads to conflict, because the model quickly develops into a rival for the object.

One major takeaway of the theory that I found very counterintuitive was that conflict arises not because we are different, but because we are the same.

According to Girard, conflict is a result of the relationship between model and subject. Conflict is the situation when both start to compete for the same object. Both model and subject try to get the same object that is accessible to both parties and cannot be shared (e.g. zero-sum games, such as first place in a race) or that the parties are unwilling to share (e.g. fame). The model becomes the obstacle and rival.

In the model-obstacle scenario, both parties act as models for each other. This drives up the desire for the object and their rivalry.

What I found interesting is that the rivalry wouldn’t need to erupt if both parties acknowledged that their desire arises from the other.

To come back to the Silicon Valley example: If Dinesh would acknowledge that he only wants better rims on his Tesla because his coworker Danny has bought a more expensive version, the rivalry would end immediately. In social hierarchies admitting that the other is a model increases the other’s social status. It also makes clear that the desired object is not important for the subject, clearing up the situation.

What actually happens is that the subject starts blaming the model-obstacle and at the same time makes sure to project originality for the desire.

I wanted it before it was cool!

Desire and Herd Behavior

As an entrepreneur, I find Girard’s theory especially applicable to marketing and fundraising.

A major marketing trend that started a couple of years ago is influencer marketing. It uses the influencer as a mediator.

The influencer is an external mediator. We, as followers, cannot become the influencer. With her two million followers, the distance between the influencer and the average follower is simply too large. The influencer presents an object. By doing so, the follower imitates the influencer in desiring that object, which ideally is converted into purchasing action.

Girard’s theory explains VC behavior in financing rounds. There are numerous posts on herd mentality in the VC industry. And my own experience certainly confirms that notion.

Herd behavior became such a large part of the culture that experienced Angel investors regularly advise founders they back that it’s crucial to create “FOMO” to get any commitment from a VC fund.

FOMO (fear of missing out) is nothing more than Girardian model-obstacle desire. In this case, the mediator is internal. The role needs to be played by another VC fund. Since all funds offer almost the same product, the distance between them is small.

The small distance provides fertile ground for model-obstacle dynamics to develop. In a funding round situation the object of desire becomes the allocation in the funding round.

As more and more early-stage venture capital funds are started following the same playbook, the distance between funds decreases. Although each fund says that they are special given the founders of the fund, the LPs or their focus, overall, they all offer the same thing. New funds imitate the older funds in trying to build a brand. Older funds imitate the newer funds in creating the image of “founder friendliness”.

The only thing that cannot be imitated is the serial entrepreneur. He has demonstrated desirability in the past by starting and selling a startup. In this market, VCs openly approach entrepreneurs, to preempt other funds and competition. The greater the rivalry between funds, the more social status the winner can generate by closing the deal.

The result is that most of the rounds that do close are oversubscribed. Hot rounds get made, others not.

Closing Thoughts and Further Reading

Despite its applicability, I wonder if mimetic desire is a now-invalid behavior that stems from the scarcity-dominated past. Desiring and competing over something only makes sense if that thing is scarce. Thus, competition would be zero-sum.

In hunter and gatherer times, if I saw somebody pursuing a rabbit, it made sense to also desire that rabbit. However, nowadays, most objects are abundant. In other words, in most cases, we can both have the same rabbit. Rivalry may be the natural response, but it doesn’t make sense any longer. I certainly try to be more conscious of these kinds of subconscious impulses and heuristics.

If you would like to read more on René Girard, I would recommend starting with articles on violenceandreligion or the website of Imitatio. Ribbonfarm provides a good critique and many counterpoints to mimetic theory.

Cover image by Andy White on Unsplash